What's in the bag?

In which I explain the acronym and we look at graphs.

Welcome to BYOB mm!

Apart from the occasional silly reference or joke, I will not talk about alcohol here.

Rather, the acronym stands for Be Your Own Building’s maintenance manager.

Yeah, that’s right. A blog series on building maintenance.

And if that's not enough to make you want to grab a stiff drink, we’ll start with theory.

Is there ever a better way to lose a reader? Probably not! But rather than just scare you with pictures of stuff which has gone horribly wrong, I aim to give you some tools that make your life easier and give you control. If you would rather look at pictures of stuff that has gone wrong horribly , Google is your friend.

Now, I am going to try and tell you that you can do this.

Maintaining your property is not hard. You don’t even need to know much, if anything, about doing actual maintenance. Do you struggle with IKEA instructions? We’ve all been there and it has zero impact on your ability to maintain your home.

Afraid of heights and therefore never going to set foot on the roof? I’ll go so far as to call that a net positive: you’re going to stay safe and hire an expert rather than try and do it yourself.

The only part that is hard about maintenance is that it is a long game. We humans are really not good at that, and our natural tendency is to shy away from it even when it stares us in the face.We’re much better with short term planning and actively look for distractions when faced with a long game. Also: it might involve spreadsheets, which again, yuck.But, spreadsheets aren't hard, they just sound really boring. But I can guarantee you that the one person you know to always win their fantasy sports league delves into data, so maybe it does actually help.

Playing the long game well (and being able to identify when and where you fucked up, pardon my french) will save you significant money down the road. That is the real reason for managing your property’s maintenance well.

To paraphrase Ramid Sethi (I will teach you how to get rich): spend outrageously on what makes you feel rich, and cut spending on what doesn’t. Spending oodles of money on maintaining your property is not going to make you feel rich. If anything, it will make you feel poor afterwards, so… let’s not adopt it as a strategy and instead, let’s organise our way to only spend what is necessary. Necessity is not a black-and-white decision, nor is it a zero-sum game. If it was, we would not have professional asset managers.

In this opening blog, I will touch upon a key concept: how the various parts of your property behave over time.

Why start with such a dry subject?

Well, it shows you that you have a choice. And when you can choose, you have control. Life doesn’t happen anymore. You’re at the least partially in the driving seat of what comes after shit hits the fan.

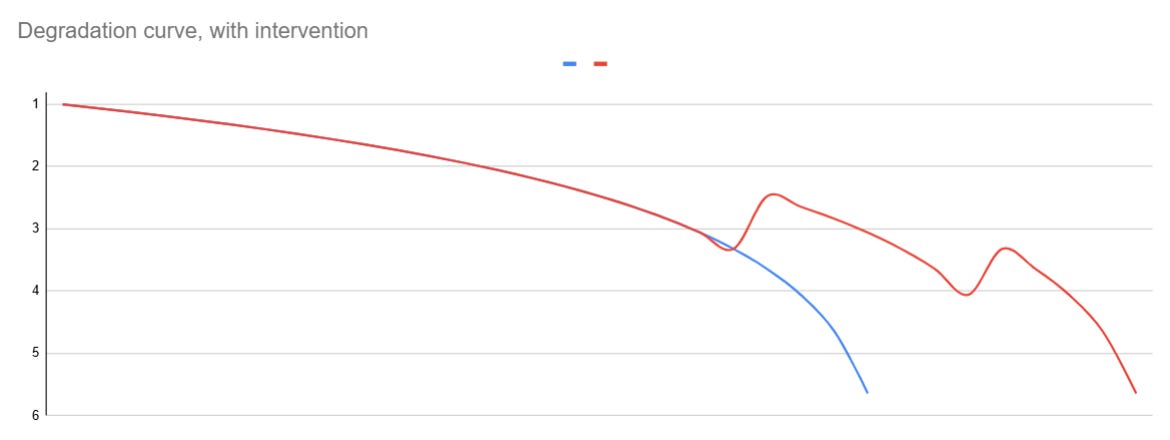

You see, the bits and bobs that your property consists of, do not degrade along a nice straight line. Instead, it’s more or less a curve, of much the same type as Wile E. Coyote missing a turn. It’s all smooth sailing along a gently bending trajectory until midway through its lifespan (the X axis), after which it plummets faster and faster down. Also, without intervention, it will never go up. To illustrate with a quick Google sheet graph using the degradation curve from the maintenance assessor’s handbook of the Dutch government’s Central Government Real Estate Agency, where it is used as a prediction of the technical quality of an unassessed component:

The 1 to 6 on the y-axis is the scale of the Dutch NEN-2767 system, which uses the full numbers as an indication of the general quality of a component. One means top notch, six is ready for replacement: if you don’t, it will just fall apart sooner rather than later. The Dutch love this particular system so much that they compile it into aggregate scores for the entire building.

So when do we maintain? Well, that is entirely up to you. It’s your choice. You’re in control. If you really want to have the Vegas experience at home of how to let a 100k slip away, try and repair every scratch, improve on everything and never ever let that degradation curve hit 1.25. It’s the boat owner’s conundrum: rich enough to buy it, not rich enough to maintain it. On the other hand, do nothing, and that’s essentially what you’ll end up with. After all, the first thing a buyer will see is the immediate need for significant investment.

Anyway, I am not going to completely dodge the ball here. No component of an asset exists in a vacuum. If your drainage pipes are full of trash and holes, it really doesn’t matter much that the paintwork on your windows is the envy of the neighbourhood. But what you can do, is to determine how far you’re willing to let certain things slide and which things you really do not want to compromise on. To kick in an open door: I advise you to put safety very high on the non-compromise list. You’d be surprised how often it’s nonetheless forgotten as an investment criterium.

Anyway, back to that curve. Immediately after its construction, the asset or component starts to degrade, but the curve starts more or less anew from the top end. Repeated maintenance thus leads to a jagged line. If you value aesthetics for example, you’ll spend time and money repeatedly in order to keep that shiny ‘as-good-as-new’ status after each intervention. Below an intervention at the halfway point of the life span, restoring to an (almost) as-good-as-new situation:

If we’re talking about a garden greenhouse, we mostly care about whether or not it keeps the warmth in and the rain out. We probably care little about whether it looks in five years time like it’s still in the showroom. In fact, we may like to see some rough patches here and there. The initial excellent state of the building when it is put up is a bonus, because it gives us time in which we just let the thing decline without interfering. We’re (at the least subconsciously) fully recognising that we will never repair it to its previous glory (and value) and that decision is probably justified. When you decide to sell your property, it seems unlikely a buyer will ever count your little tomato greenhouse as a negotiating factor in their bid. In this case, we’re much likely to intervene later, and not restoring to the new condition or even the condition of the previous renovation:

As you can see, we can make a decision on what level of degradation and depreciation we are comfortable with and the level we want to bring it back to when we intervene. We can do this for every single part of our asset, as long as we are aware of its function, cost and lifespan and can value it appropriately as a result. By monitoring the state of the asset or the component we can intervene when it threatens to fall below that level of deprecation. Naturally, it needs to be a holistic view: each component is a part of the greater structure and needs to be seen as such.

Lost already? From all the above, I want to say that the key takeaways are the following three:

Our property is made up of individual parts with individual lifespans that are all on their own S-curve as they deteriorate;

We as owners get to decide when we intervene and to what maintenance level we restore things;

We have tools to base our decisions on.

In the next blog, we will stay zoomed in. Instead of the theoretical lifespan and maintenance ‘plan’ for a single component, we’re going to be looking at the decision making of forced intervention on the same micro-level. You could call it corrective maintenance and you would be talking the talk of the professional, but it really is just dumb luck (or neglect, or a combination of both): what to do when a single asset breaks down.